A “second path” for Third-World countries

By their very nature, museums of ethnography are part of a country’s cultural relations. It is evident, taking into account that ethnology at the turn of the 20th century concentrated on studying far-away and exotic peoples rather than the society in which the science itself evolved. Nevertheless, these museums’ true mission was to make their collections available to local audiences as well as to researchers.

During the Seventies the Federal Political Department gave serious thought to the adaption of their cultural foreign policy to the so called countries of the Third World, to Sub-Saharan Africa, to be precise.

How to adapt a policy of cultural influence mainly based on the written word and well known stereotypes to culturally remote populations, oftentimes also illiterate? So far, the Service for technical cooperation had hardly taken the question of culture into account.

1976, the cultural section of the Political Department, directed by Paul Stauffer, published a report mentioning a mysterious “second path”.

What was this about? First of all this “second path” stood in direct opposition to the “first path”, an approach corresponding with cultural policy as practised since the end of the war.

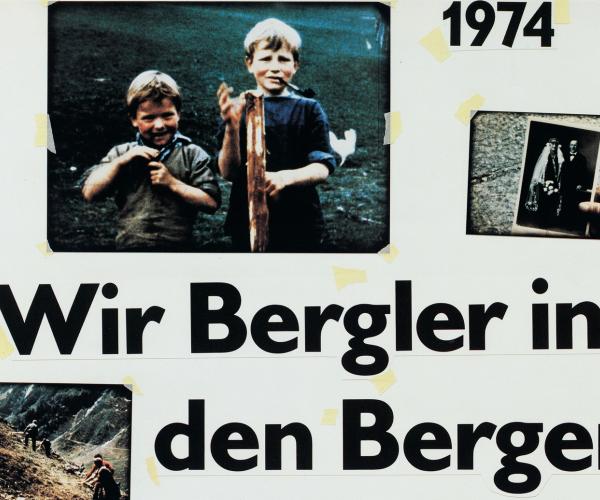

The “second path” intended to settle the problem by additionally relying on Swiss resources – museums of ethnography, and ethnologists educated in Swiss universities. Paul Stauffer presupposed that decolonised countries were in search of their own identity, originating from a cultural heritage, which needed to be reassembled. And yet, part of that heritage remained in collections in Switzerland, closely studied by more and more researchers. 1974, the Swiss Society of African Studies was founded in Geneva.

The question was not one of possible restitutions by Swiss museums, but rather one of collaborating in the development of cultural institutions in the respective countries, supported by education and the development of infrastructure. This point of view was heavily influenced by the Conference of Venice (1970), organised by UNESCO, where serious thought was given to the new concept of “cultural development” to which every country would be entitled.

In fact, the main concern was the growing awareness that a policy of cooperation could not evade the question of culture as soon as the development of projects was involved. Aware of the situation, Francesca Pomette, senior official at the Political Department stated in 1977:

“Managing to insert a cultural element [...] into our cooperation with the Third World, would be a step towards surmounting the problem that developing aid, exclusively modelled on economic and technical performance, always means a certain occidentalisation for the beneficiary countries.”

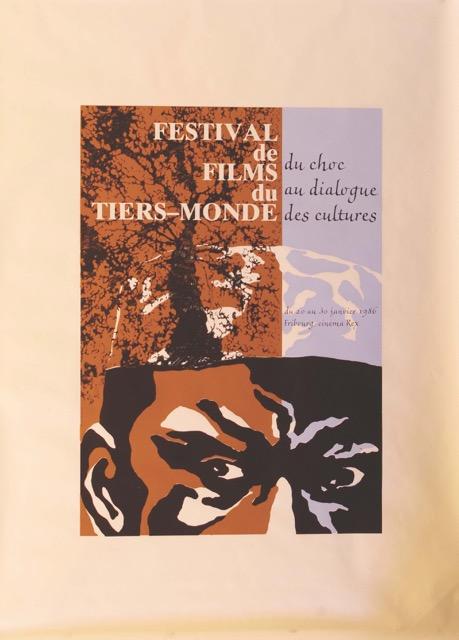

Pro Helvetia partly implemented these objectives. A “Nord-Sud” commission was put in place, supporting Third-World-Festivals in Switzerland in order to promote mutual - instead of one-way – exchange, a true dialogue between Switzerland and abroad.

An African workshop in Biel was organised for example, and the International Film Festival of Fribourg received subsidies from Pro Helvetia as well as from the Service for technical cooperation. (mg)

Archives :

Archives fédérales suisses, E 2003 (A), 1990/3/400.