Much ado about the Swiss Pavilion at the World’s Fair in Brussels

Participation in World’s Fairs prompted the Confederation to attach more importance to the export of its image. Between the end of the 19th century and the Second World War the development of Switzerland’s image made rapid progress. After that, almost 20 years passed before the next World’s Fair in Brussels, 1958.

The Brussels World’s Fair took place during the Cold War in the prosperous climate of the “Thirty Glorious Years”.

The Swiss pavilion fitted well into the overall picture, asserting traditional values compatible with those defended by the western bloc as well as the country’s part in progress and civilisation.

The Swiss business world carved out an important chunk of the pavilion for itself (3’700 square metres against 500 for the cultural section). Watch making took pride of place with the exhibition of the atomic clock and three frescoes by Hans Erni on the topic of “The Conquest of Time”.

Designed by young architect Werner Gantenbein, who was to render the same service at the World’s Fair in Montreal (1967), the pavilion was composed of juxtaposed cubicles resembling honeycombs. According to him they were meant to represent the organic life of the Swiss community, “united in diversity”, while avoiding a monumental construction contrary to Swiss customs.

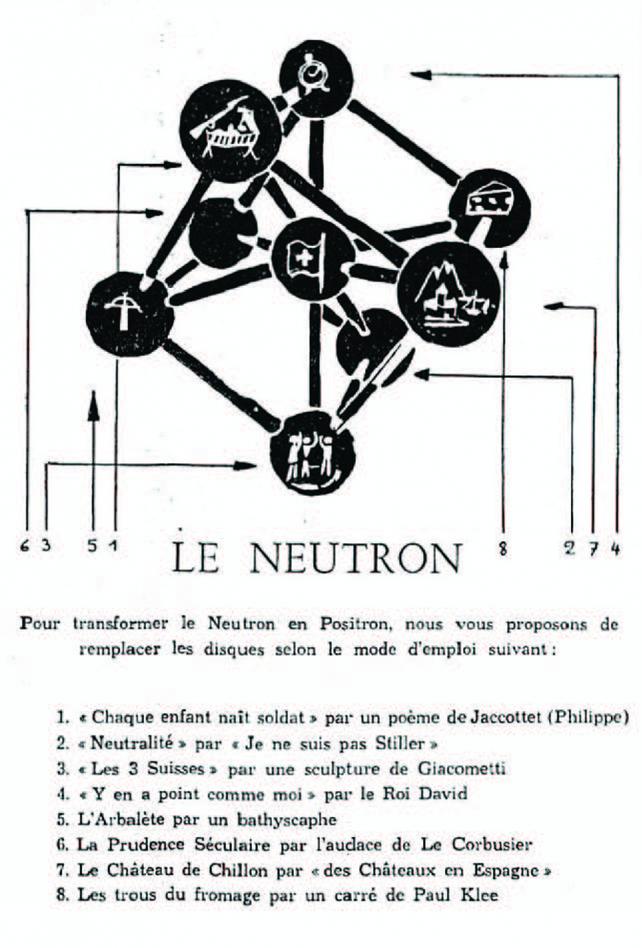

Adolf Guggenbühl was charged with drafting a first outline of the cultural section for the Swiss pavilion. Playing a little on the theme of the National Exhibition, the “Landi” of 1939, the basic idea was to show the humanisation of technological progress, which was broken down into seven stages, each presented as an exhibition and a slogan.

If the pavilion did not display major changes in the export of national representations, the cultural programme was a little more exciting. In addition to a number of traditional events and Frank Martin’s oratory “Le vin herbé”, somewhat more spicy theatre was offered, like Max Frisch’s play “Biedermann und die Brandstifter”, performed by the Schauspielhaus Zurich and Frank Jotterand’s “La fête au village”, staged by the “Compagnie des Faux-Nez”.

The organisers considered the Swiss pavilion a success (4, 5 million visitors). It may also be regarded as the last big exhibition, which claimed important political, economic and cultural resources for itself, profiting from the still broad consensus on national values, mainly in terms of identity and economic aspects.

There were rumblings behind the scenes: mutterings of certain intellectuals made themselves heard. Either they criticised modernity forgetful of the mind’s activities, like Maurice Zermatten in the “Gazette de Lausanne” (5.8.1958) on the Swiss pavilion in regard to culture: “We might come to regret remaining silent; this presentation makes us look like fools.” Or they criticised the arrangement of rigid values presented in Brussels much more radically, for example in the manner of Frank Jotterand in the same paper. National representations were somewhat more undermined at the next meeting of the same type, the National Exhibition in Lausanne, 1964.

Archives :

AFS, E2003 (A), 1971/44/850.

AFS, E9043-01, 2006/177/308.

« Der Schweizer Pavillon an der Internationalen Weltausstellung 1958 in Brüssel », in Das Werk, Bd. 45, 1958, p. 345-348.

« Ausstellungen », in Das Werk, Bd. 43, 1956, p. 115-117.

Fonds Gabus, Musée d’ethnographie Neuchâtel

Bibliography:

Jost Hans Ulrich, « Anfänge der kulturellen Aussenpolitik der Schweiz », in Altermatt Urs ; Garamvölgyi Judit (Hrsg.), Innen- und Aussenpolitik: Primat oder Interdependenz? Festschrift zum 60. Geburtstag von Walther Hofer, Bern/Stuttgart : Haupt, 1980, p. 581-590.