Paul Klee: a question of nationality

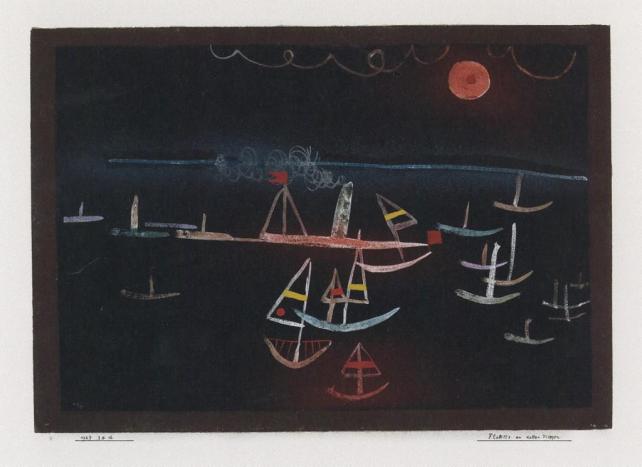

1974 was an outstanding year for the cultural impact of Switzerland in Australia. The Collegium Musicum, founded in Zurich by conductor Paul Sacher in 1941, went on a concert tour, which attracted considerable attention and enjoyed extraordinary success in Melbourne, Brisbane, Sydney, and Adelaide. In the same year, the Australian public discovered the work of a painter, today considered the icon of 20th century Swiss painting: Paul Klee. In collaboration with the Australian Arts Council, Pro Helvetia organised exhibitions in Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide that attracted large crowds.

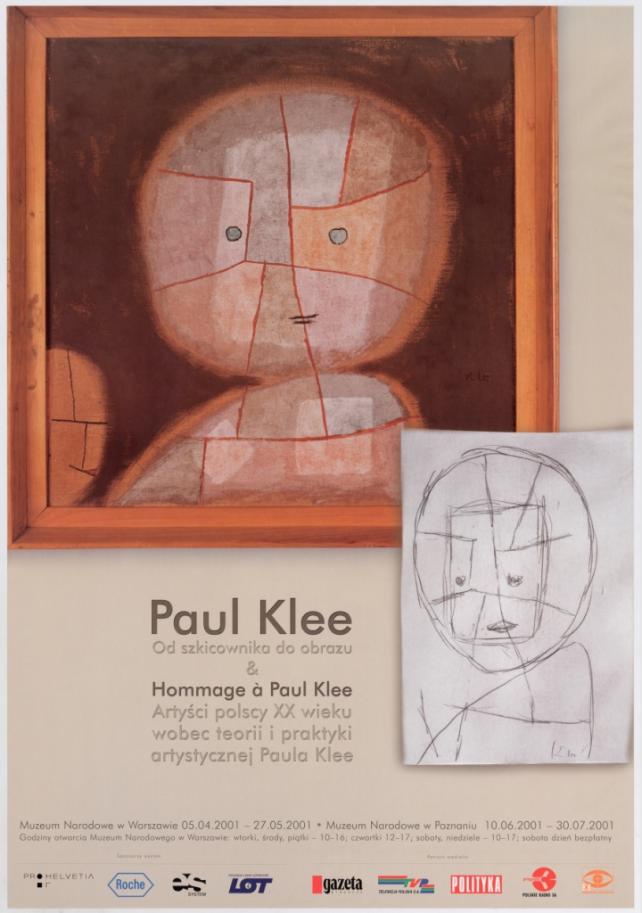

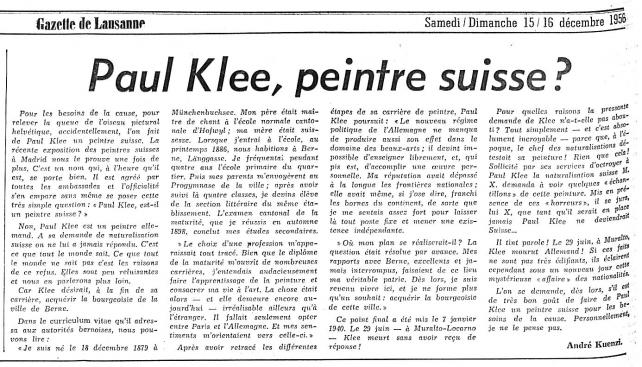

Although Klee became one of the leading ambassadors for the artistic creation in Switzerland in the 20th century, he did not always receive a warm welcome in his adoptive homeland. During the 1930s and 1940s, at the time of the Spiritual defence, his abstract works were rejected by the public and provoked sarcastic comments in the press. In 1940, the Neue Zürcher Zeitung associated them with schizophrenia. After a meticulous investigation in 1939, Klee’s application for naturalisation was rejected by police headquarters in Bern. He was considered a possible welfare case.

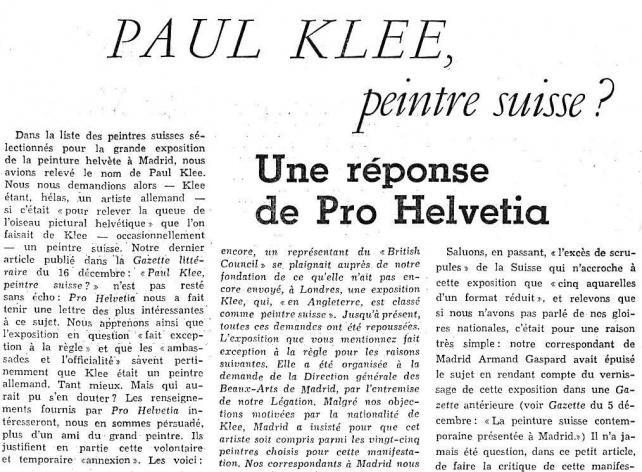

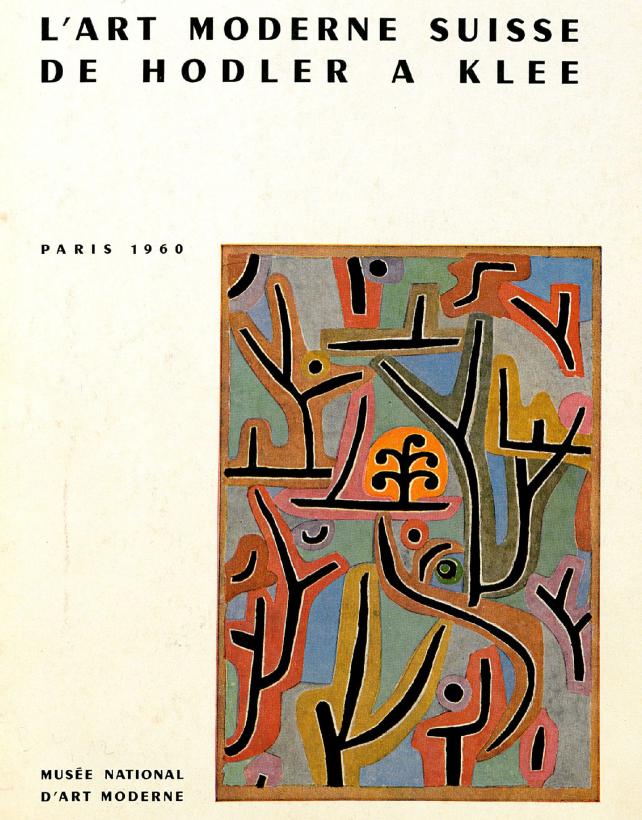

Initially also Pro Helvetia found it difficult to accept the artist, born in Münchenbuchsee, but citizen of Germany, as a representative of “Swiss art.” He died in 1940 in Locarno, Ticino, without ever having obtained Swiss nationality. In the eyes of those responsible for cultural policy in Pro Helvetia, Klee’s “Swissness” was no less in doubt than that of Russia-born, but naturalised composer Wladimir Vogel. The Federal Authorities adopted a similar position. In 1948, at the request of the Political Department, the Swiss Consulate in Los Angeles went so far as to intervene with The Los Angeles Times, who had described Klee as a Swiss painter.

Abroad, however, this position met with little sympathy. During an exhibition of Swiss contemporary art in Stockholm, the Swedish press poured scorn on it: We are looking for a name, the greatest name in Swiss modern art: Paul Klee. How could he have been overlooked, while a number of irrelevant artists were deemed worthy to represent their country? It is pathetic. And it is useless.

After that, Klee’s international prestige prevailed over any reference to his origins.

First of all, it was Pro Helvetia’s foreign press news service, which discovered Klee’s potential for successful cultural propaganda. Klee’s return to Switzerland was used to illustrate Swiss hospitality during times of political intolerance in an article, published in 1955: In 1933, when the darkness of the Nazi era descended on Germany and there was no room for free spirits like Klee, he once again turned to Switzerland [...] He was confident to find a spiritual climate he had been familiar with since youth. This certainty and a growing public awareness concerning political matters contributed to giving him a sense of security.

Finally, in 1956, Klee’s paintings were included in an exhibition Pro Helvetia showed in Madrid and Barcelona, at the invitation of the Spanish Ministry for Education, which had explicitly asked for the consideration of paintings by the artist they regarded as Swiss. At last, in the winter of 1956, Klee started his posthumous career as an ambassador of Swiss culture, which would twenty years on take his work as far as Australia. (tk)

Archives

AFS E9510.6 1991/51, Vol. 76, 277, 352

Bibliographie

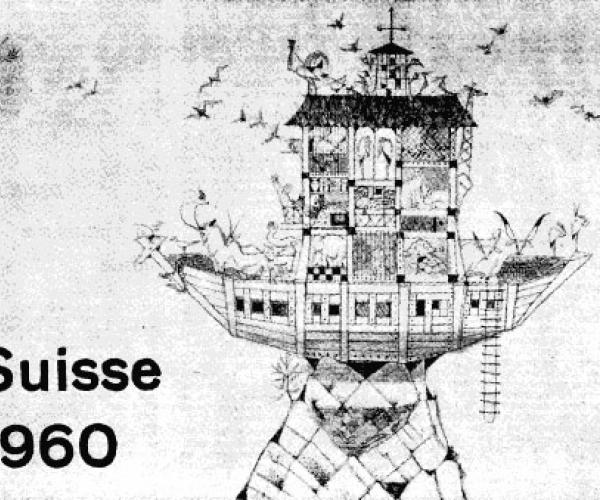

Dreissiger Jahre Schweiz, ein Jahrzehnt im Widerspruch: Ausstellung Kunsthaus Zürich, 30.10.-10.2.1982, Zurich, Kunsthaus 1981