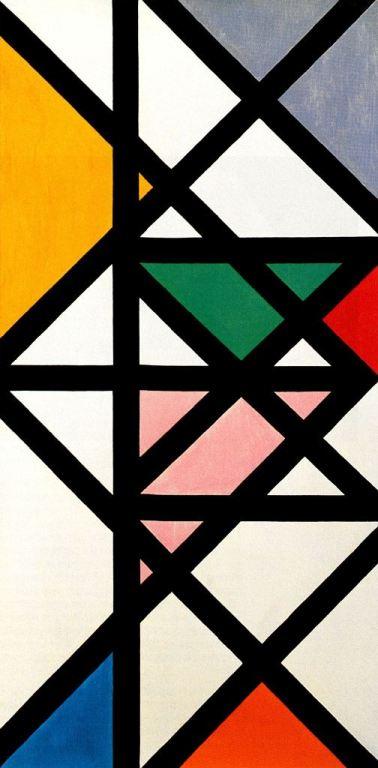

Switzerland in geometric abstraction

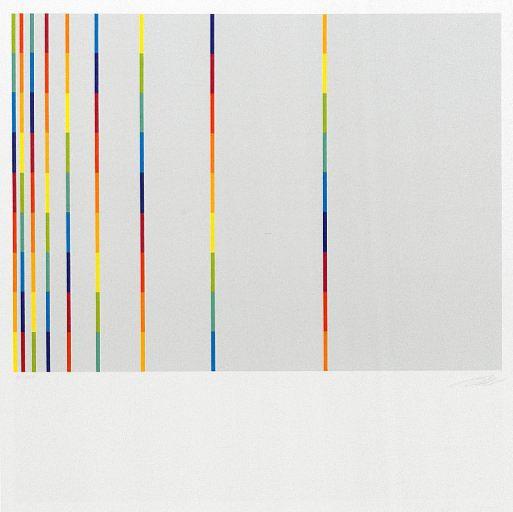

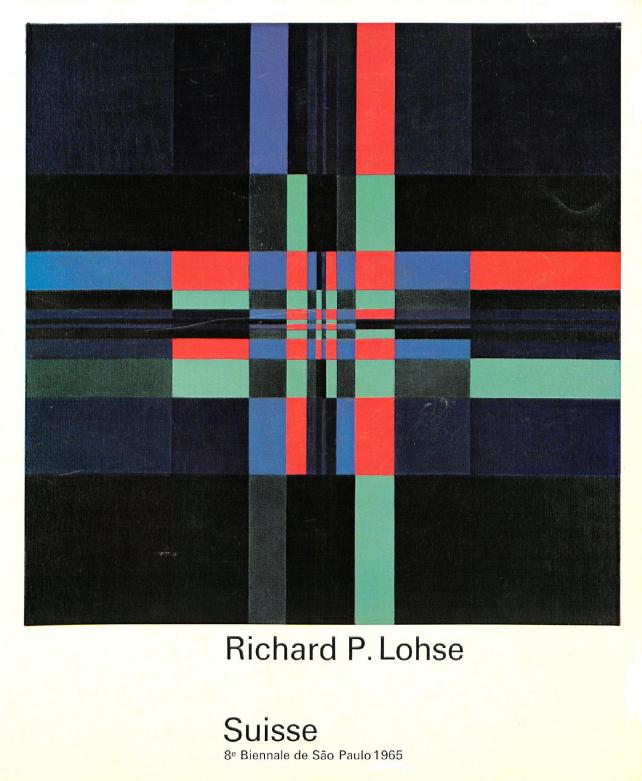

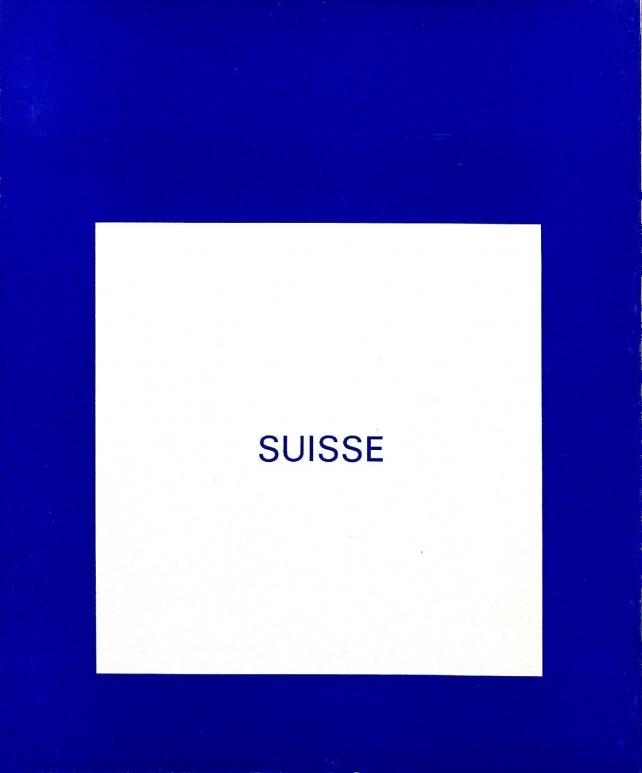

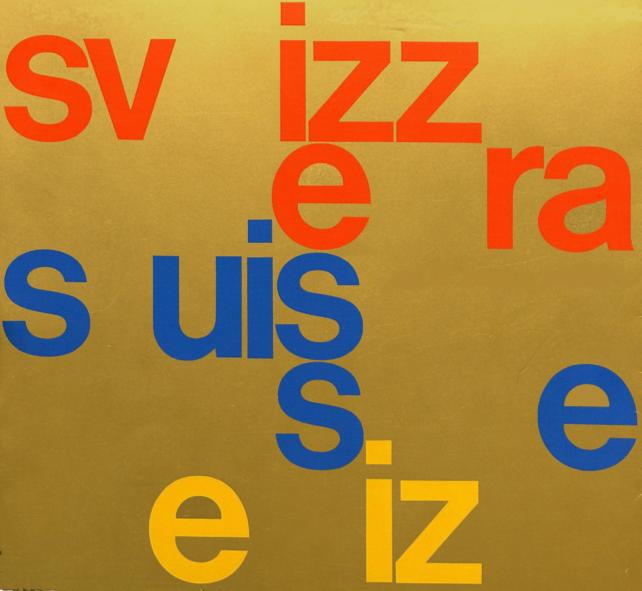

In the second half of the 20th century, Swiss art was often associated with geometric abstraction, further developed in Zurich from the 1930s on, following the German Bauhaus experiments. According to art historian Hans A. Lüthy, the “Zurich School of Concrete Art” (including artists such as Max Bill, Richard P. Lohse, Camille Graeser, and Leo Leuppi) was Switzerland’s most important contribution to 20th century art. Even if this opinion remains open to debate, it seems obvious that the sober and rational aesthetics of geometric abstraction is particularly well suited to illustrate the Swiss way.

In describing Swiss artistic creation, sobriety, accuracy, and quality of execution are long-standing stereotypes, used in and out of Switzerland. As a result, in 1929, the Swiss pavilion at the International Exhibition in Barcelona was distinguished by a simple and functional formal language, presented by Hans Hofmann, the architect responsible for the project, as an illustration of the national virtues of restraint and pragmatism.

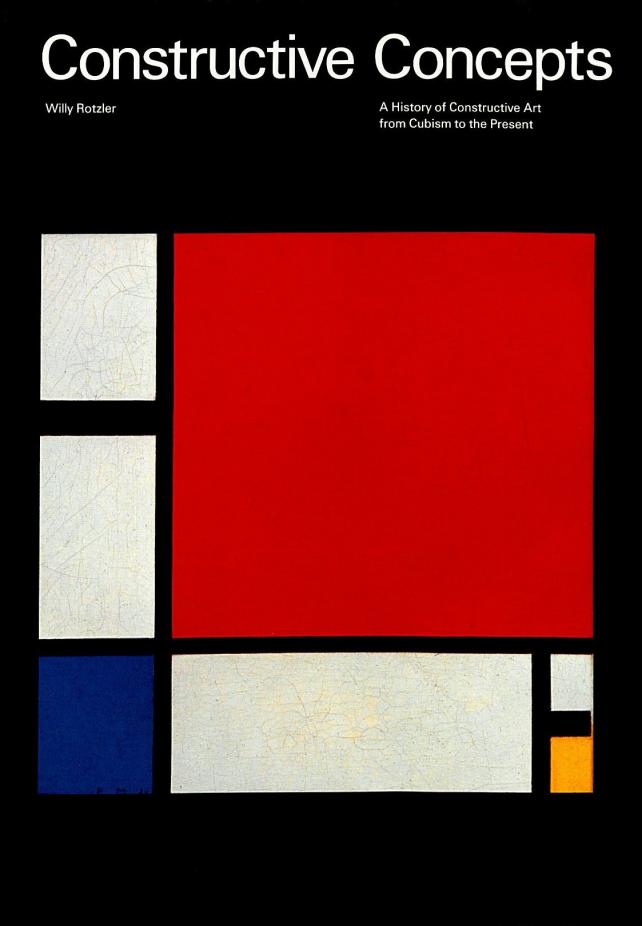

In the field of fine arts, art historian Gotthard Jedlicka highlighted in his book Zur Schweizer Malerei der Gegenwart, published in 1947, the seriousness and technical perfection characteristic of Swiss artists’ work. Even in 1982, during a conference in New York, art critic Willy Rotzler was forced to present the irrational aspects of Swiss art to the American audience in order to correct the stereotype of geometric abstraction as only form of artistic expression in Switzerland.

Unsurprisingly, the Zurich School of Concrete Art and other rational forms of abstraction played an important role in Pro Helvetia’s cultural policy. During the 1950s, the integration of geometric abstraction into foreign cultural policy coincided with its recognition by public authorities and achieving semi-official status.Artists of the Concrete Art Movement, often working in the field of industrial design and the applied arts, particularly benefited from the support of the Federal Commission for the Applied Arts.

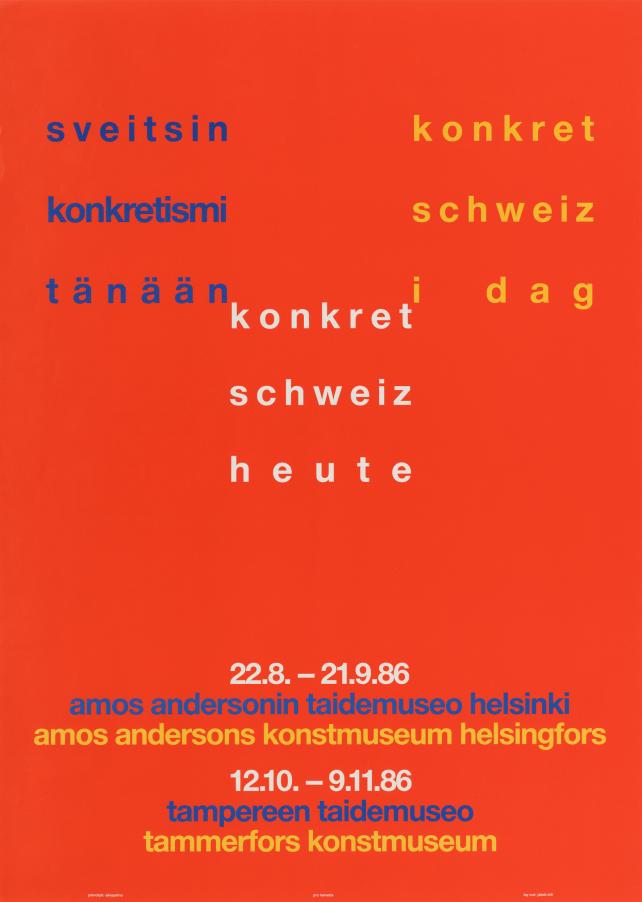

In the perception of the public abroad, geometric abstraction reinforces the idea of a country, where the aesthetic ideal is informed by an artistic language based on equilibrium and harmony. Pro Helvetia presented the works of painters of the Concrete Art movement in Berlin in 1958, New York in 1971, and at numerous retrospectives of Max Bill and other artists’ works.

In the eyes of foreign journalists and art critics, the works of the Zurich School of Concrete Art attested to the precision work often ascribed to Switzerland as well as to a puritanical mentality derived from Protestantism. In 1956, during an exhibition of Swiss contemporary paintings in Spain, the daily paper Ya referred to the legendary Swiss discipline to explain the style of abstract paintings, maintaining that for reasons connected to their very blood and nervous system, Spanish artist were incapable of reaching the same level of perfection. In 1958, in Berlin, the newspaper Telegraf even drew parallels between concrete art and the closing time of bars in Zurich. Frequently the formal perfection of the artworks was associated with the high quality of Swiss industrial products. (tk)

Archives

AFS E9510.6 1991/51, Vol. 349, 352, 888

Bibliography

Lüthy, Hans A. et Heusser, Hans-Jörg : L’Art en Suisse 1890-1980, Lausanne, Payot 1983

Omlin, Sybille: L’art en Suisse au XIXe et au XXe siècle : la création et son contexte, Zurich, Pro Helvetia 2004

Rotzler, Willy : Constructive concepts : a history of constructive art from cubism to present, Zurich, ABC-Edition 1977

Rotzler, Willy : Aus dem Tag in die Zeit. Texte zur modernen Kunst, Zurich, Offizin 1994